|

Competitive pros...

Given that the distinction between eligible and

professional skating is often drawn along the lines of sport versus

entertainment, professional competitions occupy an interesting niche

in figure skating. Although most professional skaters feel as 2002

Olympic Champion Alexei Yagudin does, that "we're here to entertain

people, that's the job for professional athletes," professional

competitions offer professional skaters the chance to engage in the

excitement of competition and give them something to work and train

towards each season.

"I

think it's nice to work towards something each year," Boitano

explained. "You get in great shape, with the feeling that competitions

are coming up."

For

Browning, the attraction of competition is that "I get nervous." He

relishes the different dimensions that professional skating has

offered him. "When I competed as an amateur, I was young and knew

nothing else. It is what you are suppose to do because you are young,

brave and healthy. When you get enough of that you want to grow as a

skater and as an entertainer. I wanted that growth and Sandra Bezic

and Stars On Ice gave that to me.. but I still loved the thrill of

competition. Being able to still flex my competitive muscle as a pro

was a gift, truly."

Even though the stakes for professional competitions are

not on the same level as eligible competition, many pro skaters still

feel stress and pressure when they compete. David Pelletier, 2002

Olympic Pairs Champion with Jamie Sale, theorized, "I guess skaters,

we've been doing this for 20 years, competing competing competing, so

as soon as you call something a competition, even though you tell

yourself, well, it's not really a competition... you know it's so

ingrained in you that it comes back. You know, the stress comes back

and you can feel the same stress that you used to feel at

competitions."

In

many ways, professional competitions are what the skaters make of

them. In the late 80s to the mid 90s, the skaters took many of the

competitions very seriously, particularly the World Professional

Championships, aka "Landover", striving to keep their level of skating

up and to continue to improve. Kurt Browning, three-time World

Professional Champion, called the World Pros "one of the most exciting

events I [have] ever been in," while six-time World Professional

Champion Brian Boitano spoke of Landover with a wistful nostalgia. "Oh

man..if you ever went to the old building in Landover...the

electricity, and it was packed, and it was just so special. It was

like the Olympics, really."

Winning one of these events may not have had the same

degree of international acclaim as winning Worlds or the Olympics, but

on a personal level, many of the skaters took real pride and almost

found a deeper personal satisfaction in their professional

accomplishments. Brian Boitano and Kristi Yamaguchi kept the bar of

professional skating high, motivating their fellow skaters to train

hard to meet and try to exceed their level of skating. In his

autobiography, Scott Hamilton speaks of how finally beating Brian

Boitano at the Gold Championships was one of the greatest nights of

his life. And Kurt Browning declares, "I have no doubt that winning

the World Pro Title over Brian Boitano was one of my proudest moments

as a skater. It was my respect for him as a person and a skater that

made it so worthy."

The decline of professional

competition...

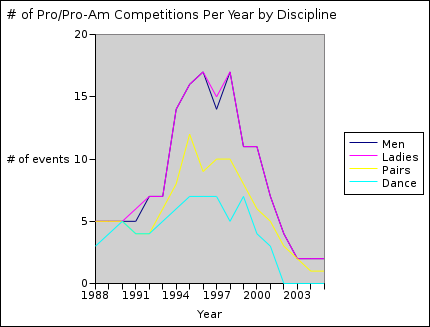

This graph tracks the number of professional and pro-am

competitions per year by discipline from 1988 until today.* Between

1994-1998, the number of competitive opportunities for professional

skaters skyrocketed. Although events like the World Professional

Championships and Challenge of Champions had existed for years,

others, such as the Canadian Pros, the Gold Championships, Ice Wars,

and the World Team Championships were all created in 1994. "Fun"

competitions like the Fox Rock 'n Roll Skating Championships, the

first installment of which was the top rated pro skating competition

ever, were also created to capitalize on skating's popularity. In the

early to mid-90s, even skaters with little international competitive

success were able to compete in many of these events and create

successful pro careers for themselves.

Then, after 1998, the pro competition bonanza dried up

abruptly. From 1999 onwards, the number of pro competitions per year

dropped precipitously until there were only two competitions

remaining. The 2002 Olympics had no effect on this drop - in fact,

the number of competitions dropped by almost 1/2 in 2002, and halved

again in 2003. While ratings had been coming down a bit from their

1994-95 high, the abrupt disappearance of so many professional

competitions in 1999 has largely been tied to two things: the

transformation of many professional events into pro-am events, and a

rapid series of acquisitions of several of the major businesses in the

pro skating world by SFX.

The advent of the pro-am...

The

1998-99 season marked a huge shift in the professional competitive

world. Dick Button saw an opportunity to integrate the pro and

amateur worlds, and began to work with the ISU and USFSA to include

amateur skaters in his Candid Productions events. These events were

among the most well-respected, and longest running competitions in the

professional world. The World Professional Championships, the US

Professional Championships, the Canadian Professional Championships,

and the Challenge of Champions all became pro-am events, which allowed

professional and amateur skaters to compete against each other with

ISU judges and modified ISU rules. To Kurt Browning, the appeal of

pro-ams in general was that, "I thought it was great to get to compete

against the guys I just watched win the Olympics. They were modified

events meaning the number of triples were limited, this made an actual

competitive event possible. They were fun."

Never a big believer in the professional/eligible

distinction in the first place, Brian Boitano's view in general of

pro-ams is that, "I think pro-am's a good idea, but if they're going

to do pro-ams, they should open up everything to being all-inclusive

and professional skaters can do the Olympics and Worlds and whatever

they want to do. If they're interested...I mean it's still the same

way I felt in '94. If they want the best of the best, then they have

to let a person who'd want to compete and thinks he can hold his own

against these other skaters to do it."

Although in concept skaters do not object to pro-am

competitions, the transformation of the major existing professional

events into pro-ams was a major sticking point for many. While the

professional competitions were very important to the professional

skaters, to the eligibles, they were just another event to add to

their schedule. This wasn't an elimination of the pro/am distinction,

it was just an incursion of the eligibles into the professional events

without reciprocation. In particular, the transition of the World

Pros, the most prestigious competition in the professional world, to a

pro-am format was cited as a major reason for the disappearance of

that event.

Boitano feels that, "Landover lost its luster when they

turned it into a pro-am. It really ruined professional

competitions. Just that one year, it just tanked. Everybody lost

complete interest, it wasn't the same thing. And I think partially

because the amateurs don't hold Landover with the esteem that

professionals do. Amateurs were just doing it, and then they would

focus on their world. I mean, this was our world every year! So it was

important to us, and it wasn't important to them, and I think the

audience could feel that."

Kurt Browning was equally emphatic when the World Pros

were brought up. "They were awesome, but Dick Button changed the

format. Alexei Yagudin competed as an amateur in it, and he never

should have. Never should have. And that's when I said 'I'm not doing

this' and I stopped. Said, you know, how can we have a World

Professional figure skating champion who is the Olympic champion, and

hasn't turned pro? That's not what we're about. We're about

professionals who tour, and train, and have integrity, and compete

against each other. And we have a World Professional Figure Skating

Championship. So that killed it too."

All

told, the pro-am experiment for the World Professional Championships

was a failure. The event was returned to an exclusively professional

format the following season, but the damage had been done. Key

skaters such as Kurt Browning and, later, Brian Boitano decided not to

return to the event, and audiences, bewildered by the concept of an

eligible skater as "World Professional Champion", lost interest. The

World Professional Championships lasted just two more years after it

became a pro-am, and then disappeared.

There's no business like show

business...

The

other half of the equation is business-driven, but may have been

influenced by the lack of interest in the pro-ams. In early 1999, SFX

bought Jefferson-Pilot Sports' Skating division, which had been

responsible for a large number of prominent televised professional

events such as Ice Wars, Men's Outdoor Skating Championships, CBS

Ryder's Ladies Skating Championships, Fox Rock 'n Roll Skating

Championships, Champions on Ice on USA, Too Hot to Skate, and the ESPN

Legends Figure Skating Championships. Then, in July 1999, SFX bought

Dick Button's Candid Productions, producers of competitions such as

World Pros, US Pros, Challenge of Champions, and the World Team

Championships. Between the two of them, JP Sports and Candid

Productions held the majority of the professional competitions in

existence at the time. These acquisitions were made in the best of

faith that SFX would continue to develop and build the events it had

acquired. However, in June 2000, ClearChannel purchased SFX, and when

the dust from all these acquisitions cleared, Ice Wars was the only

event that remained standing.

While it is easy to blame ClearChannel and SFX for failing

to follow through on the events they had acquired, the elimination of

many of these events may have been inevitable. Public interest in

figure skating in general had already begun to drop, which was only

compounded by the move to pro-ams. The business model for sports on

TV had begun to change; networks were no longer interested in paying

license fees for any but the biggest major league sports, and had

moved to a time-buy model for all other sports. As ratings started to

drop, professional figure skating moved from the license fee model to

the time-buy model, which changed the whole game.

With time-buys, the production company have to put in the

money up front to buy the time from the network, and then are

responsible themselves for bringing in sponsors and promoting the

show. Byron Allen explained, "The networks aren't willing to carry

the shows without the organizers buying the time on the networks, and

the organizers can't afford to do that unless they've got sponsors

which are willing to pay really really big bucks to do it."

Fred Boucherle explained the shifting sports content

business. "Well the sports content business went to time buys, really,

it wasn't just figure skating. It was most sports except for the major

league sports, the NFL, the NBA, the PGA. Those were the big license

fees the networks were paying. But, that's where they put all their

effort, their sales effort and their concentration, because that's

where they were spending the big bucks. And so they had to dedicate

their marketing and their sales and all their efforts to those major

rights fees that they would pay for the big leagues. So, the one-off

events, as they call a lot of the Olympic sports - the non-major

sports, they didn't have the time to sell, so they weren't interested

in spending money to buy them. And they found a business model,

because there was demand for the air time, to sell that time. And let

the entrepreneurs, or the smaller businesses who can live within those

niches to flush the money out for those sports, because they really

didn't have the time or want to put the effort in."

Steve Disson of Disson Skating is one of the few to make

this model work. Asked why he succeeds where others have not, he

answered, "Well, maybe [I'm] the only one that's crazy enough to be

willing to do a time buy." He continued, "In order for us, or

somebody to do a show like this, you have to be willing to take the

risk. Those that are involved in skating in terms of promoting aren't

maybe necessarily people in the business side. I'm not a skater or

former skater, I do it as a business, so I have a business model. And

then, I think what I do is I surround myself with a lot of good people

from the skating/artistic side and let them do their thing while I do

mine. [I'm] just focusing my attention on making it financially viable

and let other people do the artistic thing."

"The model that I have is basically I work closely with

the network to get good time slots which means, wherever I can, try to

get that late afternoon slot, and try to keep the dates of our shows

fairly consistent when they air. I look to try to get buildings to be

the local promoter to help pay me towards my time buy because it's

better...if the building has a vested interest in the event... And

then my strength is obviously I have relationships with many companies

and sponsors. No one else is willing to kind of take that risk of

doing these shows because they don't have the sponsor

relationships. And so my model has been basically that I go out and

buy the time, way in advance, and then I bring the sponsors in that

buy the time, and try to offer them fully integrated marketing

packages where it's not just that they get commercial time, but that

they get benefits of the live event and abilities to sell products and

tie in retailers and things like that."

Disson has applied his business model exclusively to

produce exhibition-style shows rather than competitions. "I think

that some of these competitions, just because the changing nature of

the marketplace, they priced themselves out and they're no longer

economically viable."

Ice

Wars, one of the two remaining professional competitions, and the only

event actually owned and developed by the network, CBS, has struggled

with just this issue. Fred Boucherle explained that exhibitions can

be done for a lot less money and production than competitions.

"Because you don't have to have scoring and judging and... And

frankly, the skaters who participate in Ice Wars, train for Ice

Wars. So they have to be paid more in order to dedicate, to devote

more time to preparing. So they're more expensive. Whether you have

prize money or whether you have appearance fees, the skaters still

expect to be compensated for their time and their effort. All these

things you don't have to do for exhibition. So the business, financial

model for exhibition is much lower. So they can be done much cheaper,

and be sold for much cheaper."

Cristi Carras, another long-time producer of Ice Wars,

also spoke about the economic challenges when sharing her view on the

decline of professional skating. "I think it has declined due to lack

of audiences, the rising cost of producing a first-class event

(travel, trucking (fuel), labor)- makes it very hard to profit when

ticket sales are not there to cover the costs. Sponsors are still

supporting the sport somewhat, but I don't think the levels are as

high, especially when the television ratings don't increase - it makes

it hard to charge a sponsor more when the tv ratings don't support the

exposure that the sponsor would like to get from their affiliation

with the sport."

Talking specifically about the challenges of producing Ice

Wars, Carras continued, "It is a year-long process, but of course most

of the work is done in the last 4-6 months prior to the event

date. The challenges are finding markets that will support the event

through ticket sales- a large grass-roots skating presence helps. It

is difficult to find a market where the consumers have not already

spent their entertainment budget on one of the skating tours or other

exhibitions."

The

cutback in the number of professional competitions was due in large

part to declining interest in the sport. The move to pro-ams, which

diminished a great deal of meaning that the competitions may have had

in the audience and skaters' eyes, was cited as one reason for this

decline in interest. Another reason often cited is the

over-saturation of the market with events that didn't really mean

anything. In the post-1994 boom, everyone wanted to get in on the

profitable skating market, and events were being created left and

right.

Boitano explained, "It's been over-saturation for so many

years, of just some really bad things on show skating. I mean in the

90s from the mid-90s to the late 90s they would buy anything that had

skating related to it. So everybody's doing like 'the Playboy bunnies

judge the skating rock 'n roll competitions' or whatever, and skaters

were being tossed money, and they would do anything. I don't think a

lot of people started making decisions based on 'well is this good for

the sport or what?'"

Aside from the economic difficulties of holding the

competitions, Disson believes that this proliferation of contrived

events contributed to the decline of the pro competitions. "I think a

lot of these competitions just weren't real, you know what I mean?

They were fake competitions. There [was] not real money on the line. I

mean, I used to be involved with the pro-am events with the USFSA when

there was real money on the line. They were all competing for it. I

just think they're contrived competitions."

Boucherle agrees that the market was oversaturated, but

contends that this is just the nature of the business, part of the

cycle, as opposed to a primary reason for skating's decline. "Well TV

does that. At least in the United States. It cannibalizes. Anything

that's successful and good, you know how it is. There will be twenty

of them coming out the next season. So it does that by nature. So it

can and it does hurt, but again, it's just another factor. But it's

more like water finding its own level, really. If there's demand, you

know it's all relative to demand. And if the demand's not there, the

supply is too great, then it's going to over-saturate the market. But

if, you know, it finds that equilibrium, as water does, then everybody

kind of survives."

In

the meantime, the producers these days are sensitive to the

accusations of over-saturation, and try to avoid them. "People have

talked about the fact that, well maybe there is too much skating on

TV, maybe they're seeing the same programs over and over," Allen said,

explaining why they chose not to air full programs from this year's

Stars on Ice show in the NBC broadcast. Disson's model of themed

one-off shows is also specifically designed with this concern in mind.

"Part of the knock used to be on skating is you see the same skaters

doing the same show numbers over and over again. There used to be way

too much skating on. Now you see the skaters in our show, they're all

theme-driven or based on the entertainers, so we do an Earth, Wind,

and Fire show that's on the tribute show, it's all the music of Earth,

Wind, and Fire. You know, these are all going to be new numbers that

the skaters learn. We have a show with Kurt Browning that's

Italian-themed with Andrea Bocelli, and you'll see new numbers in that

show. And the holiday show..so each one has a different

theme."

Previous 1 2 3 4 5 Next

|

Brian Boitano

Brian Boitano is well-known for his accomplishments on the ice. He is

the 1988 Olympic Champion, two-time World Champion, four-time US

Champion, and six-time World Professional Champion. He was elected to

the World and US Figure Skating Halls of Fame in 1996, and was the

first American skater to land a triple Axel in 1982. In addition to

his accomplishments as a figure skater on the ice, however, Boitano

has also been extremely active off the ice. He owns his own

production company, White Canvas Productions, which has produced a few

shows a year for ten years, including the Brian Boitano Skating

Spectacular, in conjunction with Disson Skating. He and Katarina

Witt also co-founded the Skating tour with Bill Graham

Presents, which was bought by IMG in 1992 and became the base for the

high production-value tour the Stars on Ice tour turned into. Boitano

says, "I think I've been involved in sort of every aspect, from

amateur skating and competing, to professional skating. I've pretty

much done everything you could do - touring, my own tour, other

people's tours, tours in tours like the Nutcracker, TV shows. I think

that I've been involved in a pretty broad place, and for 10 years have

been producing our own shows as well."

|